Department of Conservation and Recreation

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Conserve. Protect. Enjoy.

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Table of Contents

Table of ContentsIntroduction to the Third Approximation

Since the completion of the First Approximation of The Natural Communities of Virginia (Fleming et al. 2001), we have made considerable progress in the inventory and classification of Virginia's vegetation. The program's Inventory staff have documented hundreds of new significant examples of natural communities and collected thousands of vegetation plot samples. Several large multi-state regional data sets have been analyzed, making it possible to evaluate vegetation plot data in a range-wide geographic context, resulting in new and refined natural community definitions and a robust state-wide classification. DCR-DNH Ecologists have continued to develop and populate a custom vegetation plots database, designed for standard archiving and management of vegetation plot data. To date the database includes over 4700 geo-referenced vegetation plot samples from throughout Virginia, most of which are now available through VegBank, a publicly accessible database sponsored by the Ecological Society of America.

This version (Approximation 3.0) of the Natural Communities of Virginia details recent refinements to the Ecological Groups and provides additional information about the Community Types nested within each group. The Third Approximation has many more photographic images, displayed in a new format, illustrating the incredible variety of Virginia's Natural Communities. The Natural Communities of Virginia: Ecological Groups and Community Types, a companion to the DCR-DNH Ecology web pages, lists the full classification hierarchy and includes the 82 ecological groups and 308 community types currently defined for Virginia, as well as their conservation status rankings and digital links to further information. This list is available with the other natural heritage resources lists (rare plant and rare animals) and is updated every one to three years, as new information becomes available.

In addition to conceptual and nomenclatural changes to the ecological community groups, recent analysis of state-wide data has lead to nomenclatural changes in many community types. Changes to Classes, Ecological Groups, and Community types, since the publication of the 2013 list, are outlined in Appendix A of The Natural Communities of Virginia: Ecological Groups and Community Types

And finally, our choice of the nominal "Approximation" in the title of this work is meant to highlight the iterative nature of our task. Much remains to be learned about the ecological communities of Virginia. Ecological systems are not static. The technologies we use to measure, analyze, and describe the natural world continue to evolve. Progressive classification at the community type level will happen as we continue to collaborate with NatureServe, our colleagues from other state natural heritage programs, and the larger USNVC partnership.

The goal of any classification is to reduce complexity and facilitate communication. A classification of Natural Communities attempts to organize the ecological complexity of nature; that is, the complex relationships of living things with their non-living environment, into discrete classes. In turn, these classes provide ecosystem targets for inventory, mapping, research, monitoring, restoration, and conservation.

Natural Communities are central to the mission of the Division of Natural Heritage. The agency is responsible by statutory authority for documenting, protecting, and managing "the habitats of rare, threatened, or endangered plant and animal species, rare or state-significant communities, and other natural features" (section 10.1: 209-217, Code of Virginia). Natural communities are described, inventoried, and tracked using The Natural Communities of Virginia, this hierarchical classification developed by DCR-DNH Ecologists. The classification provides a framework in which to describe natural communities at a scale that is meaningful for conservation, land protection and management. Natural communities are an important tool in the work of conservation biology, facilitating the conservation of maximum biodiversity and functioning natural processes. By identifying and protecting excellent examples of all natural community types in Virginia, the majority of our native plant and animal species, including many cryptic and poorly known ones, and the ecological processes they depend on, can be conserved.

The qualitative documentation of excellent or "significant" natural community occurrences in Virginia was initiated by The Nature Conservancy in 1983, and has continued since the establishment of DCR-DNH as a state agency in 1986. Significant natural community occurrences are place-based examples of natural communities which meet community-specific criteria of size, condition, and landscape context. Exemplary natural community occurrences include the most outstanding and viable occurrences of common community types and all examples of rare community types. Assessments of rarity and quality are based on evaluations by staff ecologists, often in consultation with other knowledgeable individuals in Virginia and other states. As of early 2017, DCR-DNH has documented nearly 1400 significant community occurrences in Virginia. The DCR-DNH database of rare plant, animal, and significant natural community occurrences has supported the identification and acquisition of over 60 of natural area preserves and helps guide inventory, land use decisions, and other forms of land conservation.

For more information, see the community ecology program page.

What is an Ecological Community?

An ecological community is an assemblage of co-existing, interacting species, considered together with the physical environment and associated ecological processes, that usually recurs on the landscape. This present treatment is restricted to natural communities, those which have experienced only minimal human alteration or have recovered from anthropogenic disturbance under mostly natural regimes of species interaction and disturbance. No portion of Virginia's landscape, however, has altogether escaped modern human impacts - direct or indirect - and only a few small, isolated habitats support communities essentially unchanged from their condition before European settlement. Most of the communities treated here, while somewhat modified in composition or structure, are in mid- to late-successional stages of recovery from some form of human disturbance, such as agricultural conversion or logging. This document generally does not include early-successional communities that have experienced recent disturbance or highly modified habitats such as fields and plantation forests that are artificially maintained in an arrested stage of succession. Such communities, which cover extensive areas of Virginia, may nevertheless develop into natural systems given sufficient time and freedom from further anthropogenic disturbance. A few communities that are very rare in the state and now represented only by highly degraded examples are included because of their importance to the state's biodiversity.

The specific assemblage of plants at a site is typically closely related to abiotic factors such as bedrock type, soil chemistry, slope, aspect, and elevation. Photo © Gary P. Fleming.

The specific assemblage of plants at a site is typically closely related to abiotic factors such as bedrock type, soil chemistry, slope, aspect, and elevation. Photo © Gary P. Fleming.Classifications of natural communities can be based on numerous variables that account for the complexity we see in nature (e.g., vegetation, fauna, landforms, hydrologic regime, geography), used singly or in combination. Natural community classifications prepared by Natural Heritage ecologists for several other eastern states (e.g., North Carolina [Schafale 2012], Pennsylvania [Zimmerman et al. 2012], Vermont [Thompson and Sorensen 2000], and New York [Edinger et al. 2014) often use a "multi-factor" or biophysical approach that incorporates both biotic and abiotic elements in a community concept. Except in deepwater systems, plants have proven to be the most useful components for characterizing finer-scale communities on the landscape and providing a basis for comparing classifications covering different geographic areas. Plant species are faithful indicators of site conditions, and plant species collectively (i.e. vegetation) reflect the biological and ecological patterns across landscapes. Thus, plants are commonly used as surrogates to characterize and define ecological communities. While animals, especially invertebrates, can be very important in natural communities, they are often highly mobile, difficult to document, and found in many different ecological settings. Likewise, environmental conditions and processes encompass a spatially diverse array of factors from regional climate to site-specific moisture conditions that are impossible or excessively time- and labor-intensive to measure directly. Plants and vegetation are essentially immobile, readily measured (both directly and via remotely-sensed data), and typically reflect specific site conditions. For these reasons, a classification based on vegetation can serve to describe many (though not all) facets of biological and ecological patterns across the landscape. The United States National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) developed by NatureServe (formerly the Association for Biodiversity Information, ABI), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), and state Natural Heritage programs, in conjunction with the Vegetation Panel of the Ecological Society of America and the Federal Geographic Data Committee, delivers a comprehensive vegetation-based approach to the classification of ecological communities (Grossman et al 1998, FGDC 2008, Faber-Langendoen et al. 2009, Jennings et al. 2009).

Detailed information on the USNVC and its development can be found at USNVC.org and NatureServe

The Natural Communities of Virginia, Third Approximation, is a system by which natural communities in Virginia can be identified, named, and ranked. It has been developed by DCR-DNH ecologists and is a comprehensive, hierarchical classification of the state's vegetation and natural communities that can be applied in the field by a range of users and is linked to the national standard of the USNVC at its finest hierarchical level. Two central tenets of our classification are that (1) the basic systematic units of the classification are based on quantitative, plot-referenced data comprising full floristic composition of vegetation, and (2) these units are identified through rigorous analysis of data using multivariate techniques.

Collecting vegetation plot data at The Nature Conservancy's Piney Grove Preserve in Sussex County. Photo: © Gary Fleming.

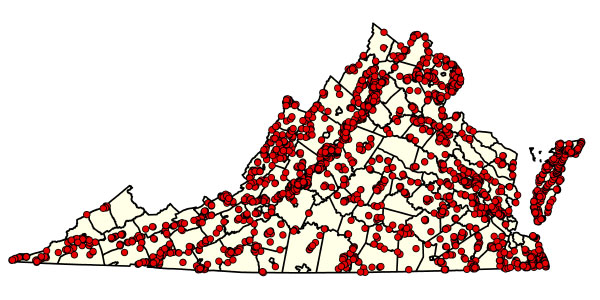

Collecting vegetation plot data at The Nature Conservancy's Piney Grove Preserve in Sussex County. Photo: © Gary Fleming.Staff ecologists began collecting quantitative vegetation data in 1989, and as of early 2017 have sampled more than 4700 plot locations across Virginia (Fig. 1). Our program is strongly committed to a "specimen-based" approach to community classification that depends on structural, floristic, and environmental plot data collected from uniform areas supporting homogeneous stands of vegetation. Although the analogy is imperfect, data from each plot could be considered a "specimen" that may be compared with other plot data in order to delimit vegetation "taxa," in much the same way as a botanist analyzes preserved plant specimens to determine the taxonomic limits of species. As a result, procedures for observing, measuring, describing, and comparing vegetation are standardized to specific scales , which facilitate more precise and objective characterization of vegetation types than is possible through purely qualitative field observation. Data for each geo-referenced vegetation plot sample are archived and managed in a customized database we call VAPLOTS, that ensures the data are standardized and available for further analysis or reanalysis in the future. A static subset of the data in VAPLOTS (without precise geocoordinates) is now available through VegBank, a publicly accessible database sponsored by the Ecological Society of America.

Fig. 1 General location of 4,758 vegetation plots sampled by DCR-DNH ecologists since 1989.

Initially, a substantial proportion of these plot data were collected as part of landscape-level studies for several discrete areas of the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests (Fleming and Moorhead 1996, Rawinski et al. 1996, Coulling and Rawinski 1999, Fleming and Moorhead 2000); the Grafton Ponds complex in York County (Rawinski 1997); three adjacent watersheds in southeastern Virginia (Fleming and Moorhead 1998); the Fort Belvoir Military Reservation (McCoy and Fleming 2000); the Pamunkey River Watershed in the northern Coastal Plain (Walton et al. 2000); the Bull Run Mountains (Fleming 2002b); Manassas National Battlefield Park (Fleming and Weber 2003); Shenandoah National Park (several projects); and the Potomac Gorge (Fleming 2007).

Over the last two decades, classification initiatives have shifted to analyses using data collected across broader geographic ranges have been undertaken, including:

These projects in addition to work on specific groups or types with our colleagues in adjoining states, have allowed us to re-examine data and results generated by the landscape-scale projects on a regional basis, and have fostered an increased understanding of the relationships between Virginia vegetation units and those proposed by other states and the USNVC.

Structure of the Virginia Natural Community Classification

The Third Approximation is structured like previous versions of The Natural Communities of Virginia. The classification is hierarchical, with each successive level organizing the units below it into groups of similar entities. The divisions of the Virginia classification hierarchy, from the top down, are:

The System is the upper-most level of the classification hierarchy. The System level is based on large-scale hydrologic regime and includes five divisions: the Terrestrial System includes all upland (non-wetland) habitats, while the Palustrine System encompasses all non-tidal wetlands dominated by woody plants and emergent herbs. The Estuarine System includes emergent and floating / submergent tidal wetlands, extending to the upstream limits of tidal influence. The Riverine System and the Marine System are each represented by a single ecological group that supports vascular plants. This system-level treatment generally follows Cowardin et al. (1979), except that freshwater tidal wetlands are included in the Estuarine System, and some communities that would be placed in the Lacustrine System of Cowardin et al. (1979) are included in the Palustrine System. Classifications of deepwater Lacustrine, Riverine, Estuarine, and Marine System communities that lack vascular plants, as well as of Subterranean System (cave) communities, are currently under study or development by other groups of specialists.

The Ecological Class is meant to aid in organizing ecological community groups and is based primarily on gross climatic, geographic, and edaphic similarities. The Ecological Class level was originally derived from the comparable level of Schafale and Weakley's (1990) Third Approximation classification of North Carolina natural communities, but names and concepts have diverged over time. We have defined 14 Ecological classes to organize the natural communities of Virginia. These classes are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but serve to group physiographically and topographically related community groups, which often co-occur on the landscape.

Terrestrial Ecological Classes

High-Elevation Forests, Grasslands, and Rock Outcrops

Low-Elevation Mesic Forests

Low-Elevation Dry and Dry-Mesic Forests

Low-Elevation Woodlands, Barrens, and Rock Outcrops

Maritime Zone Communities

Sandy Woodlands of the Inner Coastal Plain and Outer Piedmont

Alluvial Floodplain Communities

Non-Alluvial Wetlands of the Mountains

Non-Alluvial Wetlands of the Coastal Plain and Piedmont

Saturated Peatlands of the Coastal Plain

Non-Tidal Maritime Wetlands

Riverine Vegetation

Tidal Wetlands

Marine Vegetation

The Ecological Community Group is the level of the classification that organizes community types. Ecological community groups are aggregations of community types with topographic, edaphic, physiognomic, and gross floristic similarities. Community types within an ecological community group are often distributed in different regions of the state and have floristic differences that result from biogeographic influences. Community groups differ in their extent on the landscape, some are very broadly defined and have large geographic coverage (e.g., Oak / Heath Forests), while others are very narrow in concept and distribution (e.g., Piedmont Granitic Flatrocks). A few groups (e.g., Inland Salt Marshes) may have only a single occurrence in Virginia but are known to have representatives in other states. However, most Ecological Community Groups define natural communities at a relatively coarse scale that may be more appropriate for large-scale applications such as ecological modeling and vegetation mapping. In addition, they employ concepts and terminology that are communicable, familiar, and useful to a wide range of potential users.

The Community Type is the finest level of the classification system and is nested within the Ecological Community Group. Community Types are plant assemblages that exhibit similar total species composition and vegetation structure and that occur under similar habitat conditions, and, for the most part, repeat across the landscape. The Community Type level is equivalent to the Association level of the United States National Vegetation Classification System (USNVC) (Grossman et al. 1998, Jennings et al 2009, USNVC 2016) and is a concept that has been used by most of the schools of floristic classification (Whittaker 1962, Braun-Blanquet 1965, Westhoff and van der Maarel 1973, Moravec 1993). The Community Type is the level at which community inventory and conservation action are aimed and, as such, it is the level at which community occurrences are tracked and for which conservation status ranks are assigned.

The protocol for naming community types is described in the introductory section on Procedures for Collecting and Analyzing Vegetation Data.

Relationship of the Natural Communities of Virginia to the USNVC and other classification systemsSince the middle 1990s, the United States National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) has been developed and implemented first by The Nature Conservancy (TNC), and since 2001 by NatureServe, always working with the network of Natural Heritage Programs and U.S. Federal Agencies, in conjunction with the Vegetation Panel of the Ecological Society of America and the Federal Geographic Data Committee (Grossman et al 1998 , FGDC 2008 , Jennings et al. 2009). Today, this group of cooperators is known as the USNVC Partnership (USNVC 2016 ). The United States National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) is a jurisdictional subset of the larger International Vegetation Classification of Ecological Communities (IVC), which is maintained by NatureServe in an institutional database. The North American units of the IVC are posted online via NatureServe Explorer. The USNVC employs a hierarchical classification scheme that has more recently been termed the 'EcoVeg approach' (Faber-Langendoen et al. 2014, Faber-Langendoen et al. 2016 , Faber-Langendoen et al 2017). The approach, provides an 8-level hierarchy for natural types, with three upper (formation) levels, three mid (physiognomic-biogeographic-floristic) levels and 2 lower (floristic) levels, and a separate 8-level hierarchy for cultural types. The entire hierarchy has been applied to the vegetation of the United States and the types and descriptions are made available on-line through the USNVC Hierarchy Browser. The units of the two finest levels, the Alliance and Association, are maintained through the USNVC review board to ensure consistent definitions. Proposed revisions are reviewed both locally and nationally and changes are published in the Proceedings of the U.S. National Vegetation Classification.

Virginia's DCR-DNH Ecologists work in partnership with NatureServe to develop the finest floristic level of the classification, the Association. USNVC Associations are equal in scale to Community Types in The Natural Communities of Virginia classification and, for the most part, have a one-to-one relationship to the Community Type. However, Community Types have Virginia-specific names and concepts, while Associations are named and defined based on the range-wide expression of the vegetation.

Another related classification is the non-hierarchical classification of Terrestrial Ecological Systems for the United States (Comer et al. 2003). Like the Ecological Group level of the Natural Communities of Virginia, Ecological Systems are aggregations of Associations. NatureServe Explorer provides access to the Ecological Systems Classification, which has been used as the map legend for the USGS's National Gap Analysis Program, LANDFIRE Program, and The Nature Conservancy's Natural Habitats of the Northeastern United States, all ecological models which include Virginia in their coverage. The Ecological Group level in The Natural Communities of Virginia classification is similar in concept to Ecological System, but the two classification units differ in geographic scale. Ecological Groups are defined within the constraints of the state of Virginia, while Ecological Systems are regional in scope, with divisions along physiographic provinces. To illustrate this relationship, a crosswalk of The Natural Communities of Virginia to Terrestrial Ecological System Classification (Comer et. al 2003) is provided on our website at www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural-heritage/document/vaclass-system-xwalk-updateto3rdapprox.xlsxOne of the disadvantages of the "natural community" approach used in Virginia is the imperfect correspondence of community names at various levels of the classification with those used in similar classifications. For example, although we have adopted a number of names used in the North Carolina Third Approximation natural community classification (Schafale and Weakley 1990), major biogeographic differences between the two states made it impossible to do so completely, since each state has communities lacking in the other. Additionally, the colloquial application of many terms used in community nomenclature, including "bog," "fen," and "swamp," varies widely. We have addressed the latter problem by including a Glossary of Technical Terms and Abbreviations that clearly articulates our interpretation of terms that may be unfamiliar or ambiguous.

Identifying community types or ecological community groups in the field is sometimes problematic since vegetation and associated site conditions are gradational across the landscape. While the boundaries between vegetation types may be sharp in some areas, more often they are represented by broad zones of compositional and environmental transition. It is important to recognize that the DCR-DNH classification system, like other similar systems, is an attempt to partition an extremely complex set of factors into practical units for conservation, mapping, and management. Such an artificial group structure can never be perfect and there will always be environments and vegetation that are intermediate, anomalous, and/or difficult to classify.

Future Directions and Feedback

Detailed descriptions of the state Community Types are in progress. These descriptions will include information on the community's distribution, conservation status, management considerations, as well as key features that will help identify the community in the field. We plan to provide this information in a format that can be obtained via this website. In the meantime, more detailed information may be obtained by following the links to NatureServe Explorer within the web-based Ecological Group descriptions and within our downloadable community list document The Natural Communities of Virginia: Ecological Groups and Community Types .

As always, we appreciate and welcome comments or feedback on our work, as well as information or questions concerning Virginia's natural communities. Click here for contact information.

Acknowledgments

This classification is the result of work by numerous people over a period of many years. The authors thank them and regret that space and logistics preclude mentioning everyone who has contributed to our knowledge of Virginia vegetation.

A large number of current and former DCR-DNH employees and contractors have conducted or assisted with ecological field work, data analysis, and data management but special thanks are extended to Phillip Coulling, Kirsten Hazler, Barbara Gregory, Megan Rollins, Kathleen McCoy, Dean Walton, Tom Rawinski, Bill Moorhead, Shelly Parrish, Joe Weber, Chris Clampitt, Tad Zebryk, Chris Ludwig, Allen Belden, Nancy Van Alstine, Johnny Townsend, Mark Hall, Tresha White, Gina Pisoni, Catherine Johnson, Claiborne Woodall, Bill Dingus, Bryan Wender, Rebecca Wilson, Darren Loomis, Dot Field, Mike Leahy, Jennifer Allen, David Richert, Mike Lipford, and Dorothy Allard for major or sustained contributions.

Cooperators and consultants who have provided invaluable data and assistance include Harold Adams, Kadrin Anderson, Mark Anderson, Woodward Bousquet, Pete Bowman, Eric Butler, Elizabeth Byers, Kevin Caldwell, Byron Carmean, Leah Ceperley, Gwynn Crichton, Tom Dierauf, Judy Dunscomb, Tabitha Eagle, Don Gowan, Stephanie Flack, Cris Fleming, Tony Fleming, Irene Frenz, Cecil Frost, Tom Govus, Jason Harrison, Mike Hayslett, Michael Kieffer, David Knepper, Susan Leopold, Steve Martin, Robert Mueller, Leah Oliver, Ken Metzler, Erik Molleen, Doug Ogle, Greg Podniesinski, Stephanie Perles, Milo Pyne, Rick Rheinhardt, Erin Riley, Garrie Rouse, Mike Schafale, Vickie Shufer, Rod Simmons, Rob Simpson, Jocelyn Sladen, Christine Small, Charles Smith, Lesley Sneddon, Scott Southworth, Steve Stephenson, Charles (Mo) Stevens, Mary Travaglini, Jim Vanderhorst, Donna Ware, Stewart Ware, Alan Weakley, Tom Wieboldt, Hal Wiggins, Gary Williamson, and John Young.

Finally, we gratefully acknowledge our clients who have supported community inventory and documentation in Virginia in substantial ways - National Park Service: Kristen Allen, Tom Blount, Wendy Cass, Gordon Olson, Nick Fisichelli, Bryan Gorsira, Beth Johnson, Melissa Kangas, John Karish, Chris Lea, Diane Pavek, Carol Pollio, Chuck Rafkind, Brent Steury, and many others. U.S. Forest Service: John Bellemore, Steve Croy, Mike Donahue, Kenneth Hickman, Fred Huber, Lisa Nutt, Jesse Overcash, and many others. Department of Defense: Jason Applegate, Robert Dennis, Alan Dyke, York Grow, Dorothy Keough, Tim Stamps, and Robert Wheeler. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Alva Brunner. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Stephanie Brady, Lloyd Culp, Pamela Denmon, John Gallegos, Sue Rice, and John Schroer. NatureServe: Milo Pyne, Mary Russo, Lesley Sneddon, Judy Teague, Rickie White, and others. DCR Division of State Parks: Theresa Duffey. Virginia Outdoors Foundation: Leslie Grayson.

DCR-DNH Data Manager Megan Rollins collaborated with the ecology group in designing this website and is responsible for its practical implementation and iterative updates over the years. DCR IT Specialist Andy Patel designed a custom database to manage the ecological group photo galleries for the Third Approximation. We also thank all the individuals who have graciously contributed photographs to the website, especially Irvine Wilson, Hal Horwitz and Kenneth Lawless.